There’s not a lot I can say about using drones with Land Conservation that isn’t eloquently summed up by this excellent white paper by Nancy Thomas at the Geospatial Innovation Facility at UC Berkeley. If you’re looking for a thorough examination of the many factors that go into using drones and other aerial imagery, then I encourage you to give it a read. However, as a licensed drone pilot and easement monitor for the Trustees of Reservations here in Massachusetts from 2017-2020, I had the opportunity to really dig into the technology and identify some strengths and weaknesses. Here are some of my main takeaways from that experience:

- Drones create a lot of data.

Whether it’s high resolution videos, orthoimagery rasters obtained with something like Drone2Map, or simply aerial photographs, the output of a drone after a single mission is usually measured in Gigabytes, not Megabytes. If your existing storage system (whether it be a hard drive or cloud system) is not set up to accommodate this influx, then take the time to set up an organized (preferably by Property/Stewardship Site) file system. A reminder here that your Landscape account comes with 100GB of storage, with more available for a nominal fee. There are also account settings which you can use to handle automatic resizing of images. - For baselines and current conditions reports, there’s nothing better.

Baselines are all about capturing as much details of the conditions on the ground as possible, as you never know which photo will serve as a key reference point sometime in the future. For this reason, the ability of a drone to capture more details with a single photo is unparalleled and make them a fantastic tool for the job. - Hire a drone operator to fly a couple of missions for you before you invest in the time and money required to get an in-house drone program off the ground.

A licensed and experienced drone pilot will know how to plan a flight, fly safely, and get you the photos or materials you require. Plan a mission with them and define deliverables ahead of time. If they haven’t done conservation work, they are likely unfamiliar with much of the terminology and will need very clear instructions about what to get. For example, provide them with a map of the property complete with intended photo points and desired headings. Watching the pilot in action and dealing with the subsequent data is a great way to get some firsthand knowledge and will help you identify potential issues with starting up your own in-house drone program.

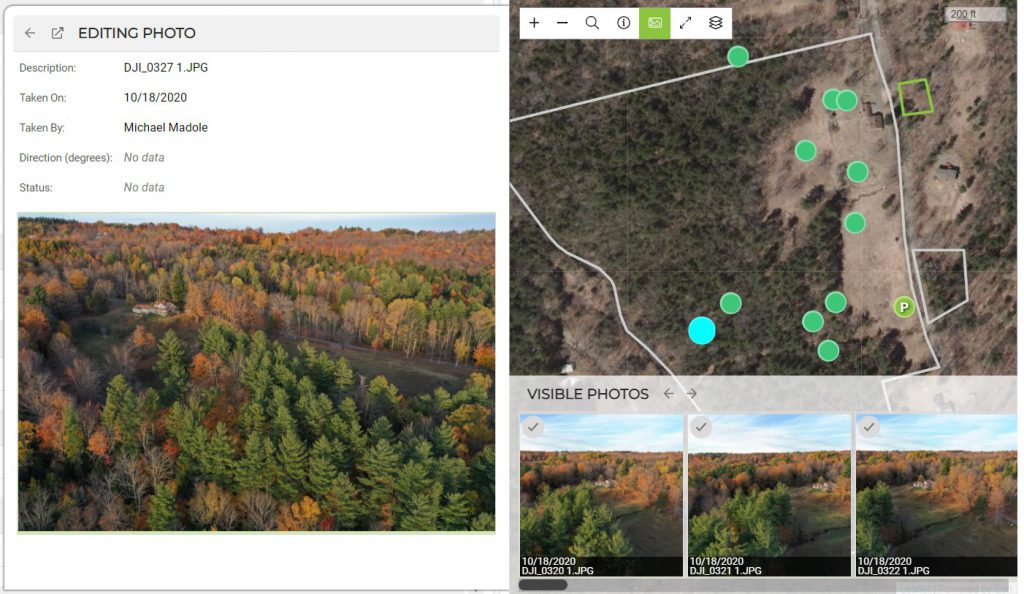

In Landscape you can easily import geotagged drone photos into a site visit record by following the workflow in this help article. After adding descriptions and number points, that data can easily be merged into a baseline or site visit report.